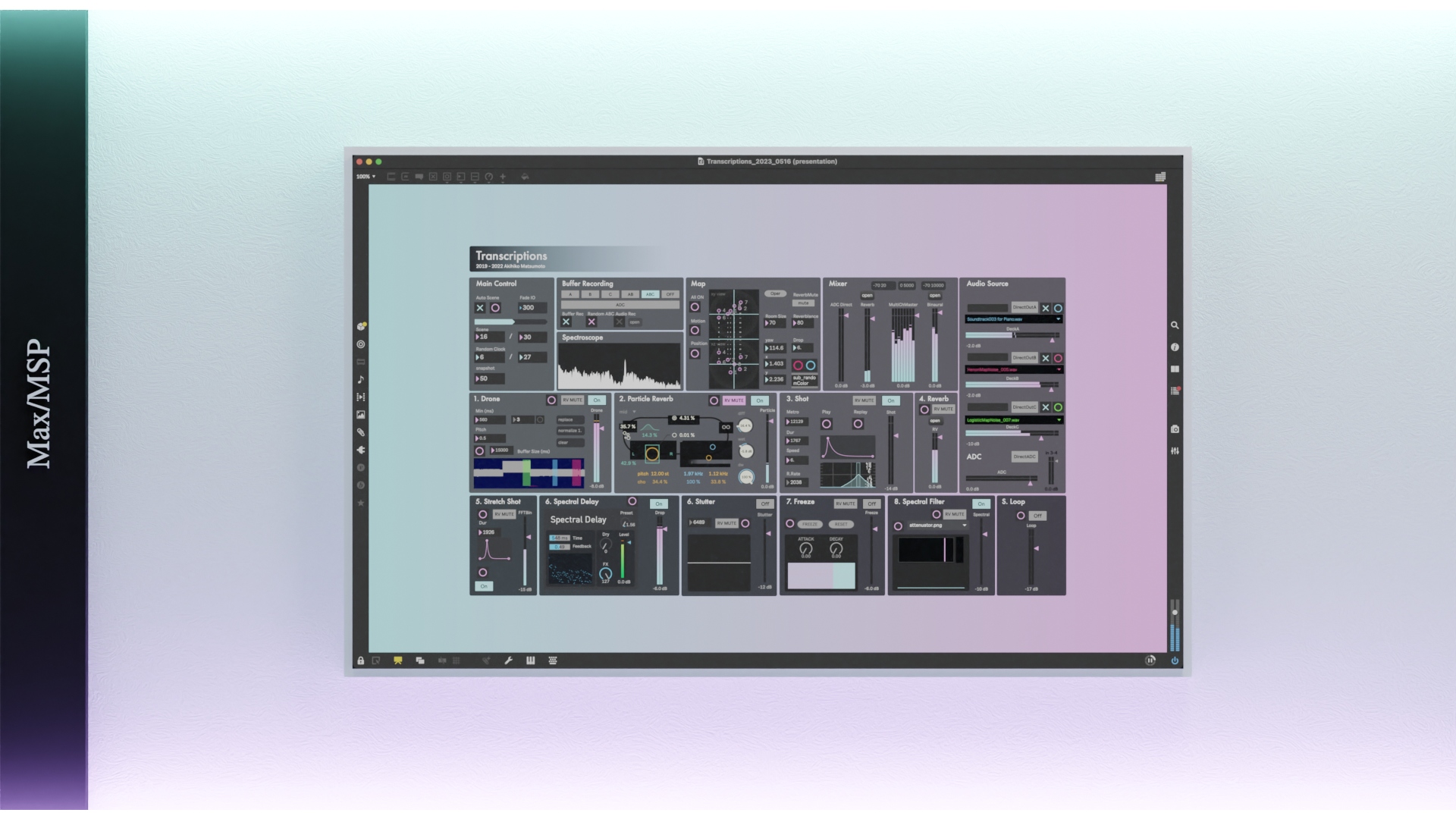

Generation & Composition

As we enter the 2020s, artificial intelligence (AI) technology is becoming more common in

music.

Now that music is being created without the need for people to create it, it is necessary to redefine

rights, originality, and creativity, which have not been considered in the past, and musicians may be asked

what they create and for whom.

The creation of music by machines is sometimes considered separately from traditional composition and called

generation, since it is sometimes created by a program or algorithm that computes instead of a human

brain.

However, what is produced is music in both cases.

Is there really a difference between generation and composition?

In this page, we will consider the fundamental question of what creativity means in music,

looking back at the history of composition in Western music from the Middle Ages to see what is different

and what is the same between traditional composition and machine generation.

2020年代に入り人工知能=AIの技術は音楽の世界でも一般的になりつつあります。人が作らなくても音楽は生まれてくる現在、これまで検討されていなかった権利やオリジナリティー、クリエイティビティーの再定義も必要になっており、音楽家も誰のために何を作るのかが問われてるのではないでしょうか。

機械による音楽の創作は、人間の頭脳に変わってプログラムやアルゴリズムが計算して生み出すこともあり、従来の作曲とは分けて考えられ生成と呼ばれます。しかし、生み出されるものは両方とも音楽です。

本当に生成と作曲は異なるものでしょうか?

このページでは音楽の世界での創造性とは何かという根源的な問題について、伝統的な作曲と機械による生成は何が異なり何が同じであるのかを西洋音楽の作曲の歴史を中世から振り返りながら考えてみたいと思います。

History of Composition

作曲の歴史

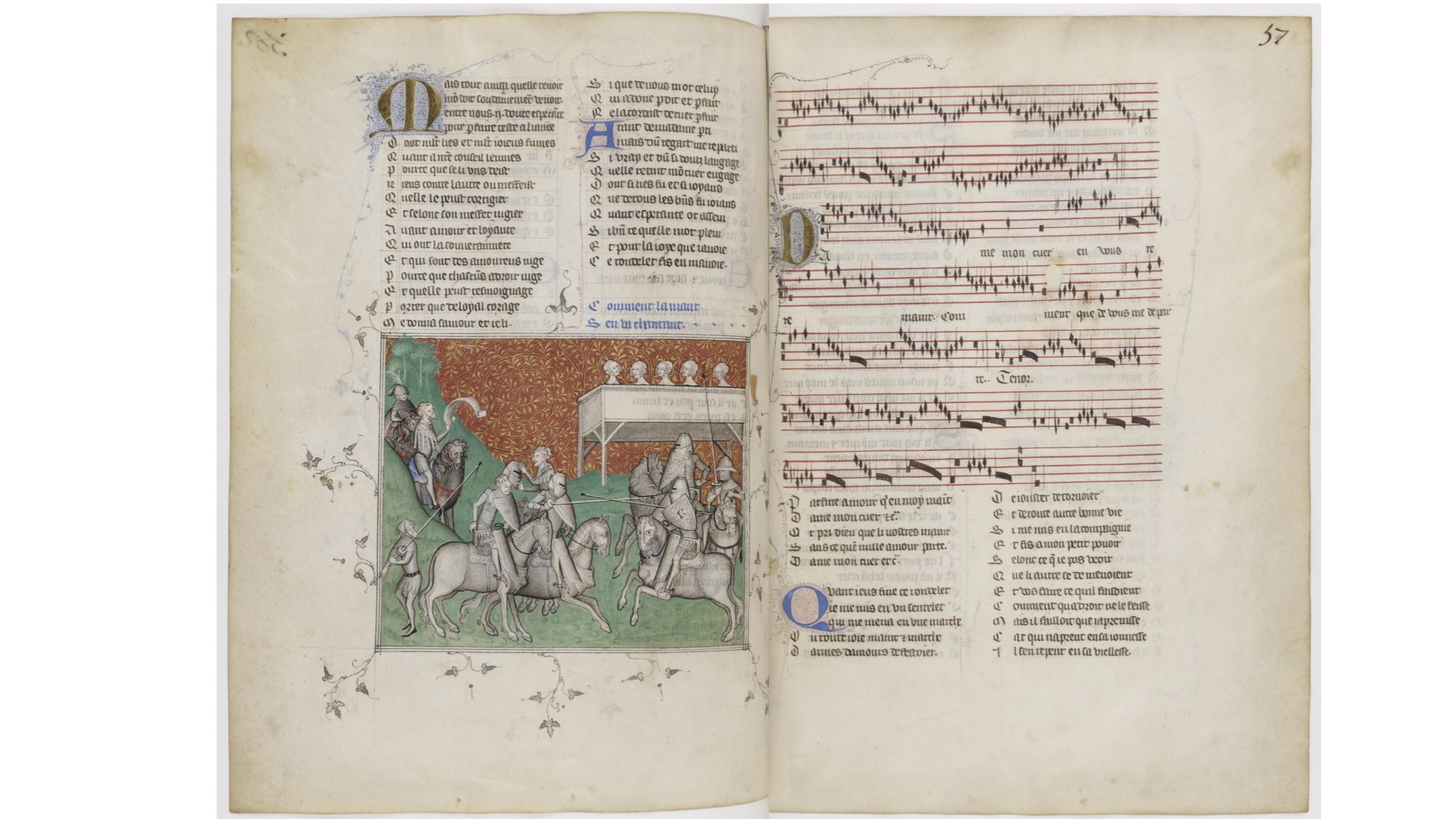

ca. 1350-1355,France (Paris),Author : Guillaume de Machaut, Title :Poésies, Remède de Fortune.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8449043q

The history of compositional techniques runs parallel to the history of human music.

Knowing the history of composition may be a guide to imagining where music is going today and how the future

may change.

Western music can be traced back as far as the monophonic Gregorian chant of the 9th century, but at that

time the author was unknown and the concept of a composer had not yet become independent.

Music meant

singing a chant that already existed.

It is said that the first composer in history to consciously assign a value to his work by naming it as the

author and releasing a manuscript of his work before his death was Guillaume de Machaut in 14th century

France.

Since then, it has become common practice for composers to write their names on the scores of their works.

Since the Middle Ages, compositional techniques have evolved from monophonic to polyphonic music in which

multiple melodies are played simultaneously, reaching its peak in the 16th century.

Then, from the 17th

century, there was a shift to tonal harmony music, which is driven by the linking of chords that have a

function.

From the 20th century onward, even a single composer wrote works in a variety of styles. It is no longer

unusual to find music in which neither melody nor rhythm exists, and we have reached the present day.

作曲の技法の歴史は人類の音楽の歴史と並走しています。

作曲の歴史を知ることは、今現在の音楽がどのような方向に向かっているのか、未来がどのように変化していくのかを想像するためのガイドになるかもしれません。

西洋音楽を遡ると古くは9世紀の単旋律のグレゴリオ聖歌に辿り着きますがこの時代は作者は不明で、まだ作曲家という概念は自立していません。音楽とは既に存在している聖歌を歌うことを意味していました。

歴史上はじめて作品に作者として名前を記し、自作をまとめた写本を生前にリリースし、意識的に価値づけを行なった作曲家は14世紀のフランスのギョーム・ド・マショーからと言われています。

これ以降作曲家が自分の作品の楽譜に署名することは一般化していきます。

作曲技法は中世以降、単旋律から複数の旋律が同時に奏でられる多声音楽へ進化し16世紀に頂点を迎えます。そして機能を持った和音の連結で推進していく17世紀からの調性和声の音楽へとシフトします。

メロディ、リズム、ハーモニーを音楽の三要素と定義できるのも17-19世紀にかけてです。20世紀以降は一人の作曲家でもさまざまな様式で作品を書く時代へ突入し、メロディーもリズムも無い音楽は珍しくなくなり現代に至ります。

Middle Age

中世

Viderunt Omnes, Léonin (fl. 1135s–1201).

In the first period when music became polyphonic, composition was considered to be the writing of melodies

in the upper part of the tenor fixed melody, which was a long-note stretched version of the existing

Gregorian chant.

Creating original music from scratch was not considered composition.

Cantus firmus is not audible in the original chant, but the values of not finding beauty only in what is

audible, as is the case in atonal music of the 20th century, were already perfected in this period.

The range of harmonic intervals in music up to the Middle Ages was also different from that of today.

For example, the third degree interval, which is essential for creating beautiful harmonies in the modern

age, was considered a dissonant interval in the past.

The support base of musicians of this period was the catholic church.

The definition of what is beautiful is

not so much a universal aural truth as it is changing with the demands of the authorities of the time.

音楽が多声化した最初の時期の作曲とは既存のグレゴリオ聖歌を長い音符で引き延ばしたテノールの定旋律の上声部に、メロディーを書く

こととされていました。

オリジナルな音楽を一から生み出すことは作曲とはみなされませんでした。

定旋律は元の聖歌には聴こえませんが聴こえているものにだけ美を見出すわけではない20世紀の無調音楽にも見られるような価値観はこの時点で既に完成しています。

また、中世までの音楽では現代とは協和音程の範囲も異なります。

例えば三度音程は現代に美しいハーモニーを作り出す上で欠かせない音程ですが、過去には不協和音程とされていました。

この時代の音楽家の支持基盤はカソリック教会です。何を美しいとするかの定義は普遍的な聴覚の真理というほどのものではなく、その時代の権力者の要求とともに変化しているのです。

The Renaissance

ルネサンス

Missa Papae Marcelli (1562), Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525 – 1594).

The Renaissance period marks the pinnacle of polyphonic musical technique. One of the most important concepts to emerge from this period is that of imitation. A single melodic theme is alternately passed on to multiple voices in different time periods, creating dialogue and interaction, with the effect of solidifying the unified musical idea as a whole.

In the 16th century, when the composer belonged to the church and was greatly influenced by it, the

Reformation was taking place and the power of Catholicism was threatened, and clear, simple music that the

whole congregation could sing was preferred over complex polyphony with many voices in a trained choir.

The composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, fearing that church censorship would cause music to revert to

monophony, began writing masses in four voices, with clearly audible lyrics, and this led to the tonal music

of the Baroque and Classical periods that followed.

ルネサンスの時代はポリフォニー音楽の技巧の頂点を迎えます。この時代に生まれた概念で重要なものは通模倣様式という概念です。一つのメロディの主題を複数の声部で時間差を持たせながら交互に受け渡し、対話や相互作用を生みながら全体として統一された楽想が強固なものになる効果があります。

作曲家が教会に所属し大きな影響を受けていた16世紀には宗教改革が行われカソリックの力が脅かされた時代であり、訓練された聖歌隊の多数の声部からなる複雑なポリフォニーより、会衆全員が歌える明瞭で素朴な音楽が好まれるようになります。

作曲家パレストリーナは教会の検閲により音楽が単旋律だけに逆戻りすることを危惧し、歌詞が明瞭に聞き取れる四声のミサを書くようになり、これがのちのバロック、古典派の時代の調性音楽に繋がっていきます。

The Baroque

バロック

The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp minor, BWV 849 (1722), Johann Sebastian Bach (c.1685 – 1750)

The Baroque period of the 17th century, when the weakened church was replaced by royalty and nobility who

became patrons of composers in order to exert their power, replaced polyphonic music that continued until

the Renaissance and evolved into a form of single melody plus chordal accompaniment in order to give it

narrative and passionate expression.

As musical instruments developed, a style of instrumentation other than that of song accompaniment began to

be explored. A style called "basso continuo," in which players improvise within the rules of the score by

adding ornaments to the bass line, was born, and the concerto and chamber music forms that are used today

developed.

The leading composer of this period was Claudio Monteverdi, who distinguished between the former and the

latter, regarding the former as Prima pratica and the latter as Seconda pratica.

After the Baroque, music became more harmonic, and harmony, which until the Renaissance had arisen as a side

effect of the layering of melodies, changed to the idea of progression through the concatenation of

vertically stacked chords.

弱体化した教会に変わり、王族や貴族が権力を誇示するために作曲家のパトロンとになった17世紀バロック時代はルネサンスまで続いた多声音楽に変わり、物語性や情熱的な表現を持たせるために単一のメロディー+和音の伴奏という形態に進化します。

楽器が発展し、この時代から歌の伴奏という地位ではない楽器のあり方が模索されます。和音における根音が書かれたベースラインの楽譜上には、和音の種類を示す数字が付けられそれに従って奏者が装飾を加えながらルールの範囲内で即興演奏する通奏低音と呼ばれるスタイルが誕生し、今日に通じる協奏曲や室内楽の形式が発展します。

この時代の代表的な作曲家はクラウディオ・モンテヴェルディであり、前者を第一作法、後者を第二作法と捉えて区別しました。

バロック以降、音楽は和声化し、ルネサンスまではメロディーを積み重ねた結果、副次的に生じていた和声は、縦の積み重なりの和音の連結により進行させる考え方へ変化します。

Classic / Romantic

古典派・ロマン派

Tristan und Isolde (1865), Richard Wagner (c.1813 – 1883).

The era that most people associate with classical music is probably the Romantic period of the 19th

century.

Composers became financially independent from both the church and the aristocracy, and were able to publish

scores and perform them publicly according to their own plans, and harmony became more complex toward the

19th century, when it became possible to express oneself musically.

Romantic composers attempted to break the norms of traditional forms and structures. This led to extensions

and transformations of traditional harmony and form.

多くの人がクラシック音楽として連想する時代は19世紀のロマン派の時代の作品ではないでしょうか。

19世紀にようやく今日的な意味での芸術という概念が誕生し、着席して静かに音楽を聴くコンサートの慣習が生まれ、音楽大学が誕生し音楽家のための専門教育が始まったのもこの時代です。

作曲家が教会からも貴族からも経済的に自立し、自らの企画で楽譜の出版や公開演奏が可能になり、音楽的にも自己表現が可能になった19世紀に向けて和声も複雑化します。

ロマン派の作曲家たちは、従来の形式や構造にとらわれず、規範を破ることを試みました。これにより、伝統的な和声や形式の拡張や変容が起こりました。

Modern / Contemporary

近現代

Rite of Spring – Sacrificial Dance(1913), Igor Stravinsky (c.1882 – 1971).

The music of Igor Stravinsky, with its multiple tonalities and complexities, has been the subject of riots between those who thought it was new music and those who felt that it was not. The expansion of music never stopped, leading to the atonal music of the 20th century, which removes the center of gravity from music by treating all 12 notes of an octave as equivalent.

Furthermore, after Thomas Edison's invention of recording technology in the 19th century, music became more

accessible to the public, and popular music became the dominant form of music listening.

Composers were able to modify their works by listening to the sound, and creativity and the spirit of

experimentation expanded.

Since the democratization of computers, various electroacoustic experiments and works have become easily

accessible to the public, and the evolution is ongoing.

The real history of popular music, which is slightly different from that of secular music in the

pre-democratic era when no records were kept, and before the invention of recording technology and the

Internet, may have just begun.

Understanding how classical music composition has evolved in relation to society may help us predict the

future.

複数の調性が並走するストライヴィンスキーの音楽は春の祭典の初演時にこれが新しい音楽だとする人たちと、これは音楽ではないと感じた人たちとの間で暴動が起きています。

音楽の拡張は止まることを知らず、1オクターブの12音を全て等価に扱うことで音楽から重心を取り除く20世紀の無調音楽に至ります。

しかし音楽史最大の出来事は二つの世界大戦でしょう。作品に戦争や社会的不安は反映され、1930年代から1940年代にかけて、ナチス政権は「退廃音楽」を弾圧し、展示会や演奏会での演奏を禁止し、時には作品の破壊を行いました。大戦はストラヴィンスキー、バルトーク、シェーンベルクら多くの音楽家を国外に追いやり、移住先であるアメリカにて異なる文化や音楽様式との出会いをもたらし、20世紀のアメリカの音楽を多様化させました。

さらには19世紀エジソンの録音技術の発明以降は音楽はより人々の身近なものとなり、ポピュラー音楽が人々の音楽鑑賞の主流になります。

作曲家は音を聴きながら作品を修正していくことが可能になり創造性や実験精神は拡張しました。

コンピューターの民主化以降はさまざまな電子音響的試行錯誤や作品の公開が手軽に可能になり、進化は現在進行形です。

記録が残っていない民主主義以前の時代、録音技術やインターネットの発明以前の世俗音楽とは少し異なるポピュラー音楽の本当の歴史はまだ始まったばかりかもしれません。

社会との関係性の中でクラシック音楽の作曲がどう進化してきたのかを知ることは未来を予想することにつながるかもしれません。

Changes in Music Listening

音楽鑑賞の変化

Music is an art completed not only through composition and performance, but also through listening. Next, we will look at how the environment for listening to music has evolved.

Music until the Renaissance was religious music for liturgical purposes in churches and music for social

occasions of the nobility during the Baroque period, and it was not until the 17th century that theaters

were born and public performances became available for the general public to enjoy.

Until the 18th century, when classical music was contemporaneous music, the subject of the repertoire of

works performed did not extend back hundreds of years.

Johannes Tinctoris, a Renaissance music theorist who defined composition and improvisation separately and

wrote numerous books on counterpoint and music theory, wrote in a 1477 treatise that there is no older work

worth hearing than those created in the last 40 years.

https://earlymusictheory.org/Tinctoris/Tinctoris/BiographicalOutline/

This is an unthinkable value in today's classical music concert culture, where performances of works by

composers who were active hundreds of years ago are taken for granted, and one can imagine that the

definition

of what is musical and what is creative has always changed with the times.

s

Popular music, on the other hand, may not be as ingrained in the culture of recycling past works as

classical

music.

The 19th century composer Felix Mendelssohn was the first to rewrite the centuries-old music industry

practice of not performing works from the past.

His arrangement and restaging of J.S.Bach's Matthew Passion for that era led to the rediscovery of Bach as a

composer and his worldwide recognition, but before that, Bach was a forgotten figure who was only

appreciated in a few regions.

Since then, classical music has become, and continues to be, a practice of re-performing works from the past

over and above the works of living composers of the same era.

However, classical music has not been a long tradition in the long history of Western music since the

Romanticism of the 19th century, when it became a culture of performing music from the past.

Since the invention of recording technology by Thomas Edison at the end of the 19th century, music has been

recorded and sold, allowing more people to experience and enjoy the works of composers.

This has facilitated

the spread of a composer's influence and fame throughout the world and has helped music to take root in the

lives of more and more people.

Recording technology has also contributed as a means of recording and preserving the performances of past

composers and performers.

Historical recordings have become a valuable resource for future generations of composers and play an

important role in understanding musical traditions and evolution.

In the 21st century, streaming playback over the Internet has become widespread, and now that the option of

music appreciation that does not depend on live performers has become commonplace, what kind of music

experience are people looking for?

With such a vast amount of past works available and the ability to immediately play back recordings, why

create new music?

Furthermore, are musicians really expected to create music in a situation where AI is creating works with a

higher degree of perfection at a speed that surpasses that of humans?

It is hard to imagine the culture of music disappearing from the world, but there are so many recordings of

musical works that even if we keep playing Spotify and Apple Music until we die, we will not be able to

listen to them all.

In this age of music, what are the activities that should be undertaken by musicians who are experts in

music?

音楽は作曲、演奏だけでなく聴くことを通じて完成する芸術です。次に音楽を聴く環境がどう進化してきたのかを見ていきます。

ルネサンスまでの音楽は教会での典礼を目的とした宗教音楽、バロック時代の貴族の社交の場のための音楽を経て、劇場が誕生し公開演奏を一般の市民が鑑賞できるようになったのは17世紀からです。

クラシック音楽が同時代音楽であった18世紀までは作品の上演レパートリーの対象を何百年も前まで遡るようなことはありませんでした。

作曲と即興演奏を区別して定義し、対位法や音楽論に関する多数の著書を残したルネサンス期の音楽理論家、Johannes

Tinctorisは1477年の論文に過去40年間に創作された作品より古い時代に聴く価値がある作品など存在しないと記しています。

何百年も前に活躍していた作曲家の作品の演奏が平然と行われる現代のクラシック音楽のコンサート文化からは考えられない価値観であり、何が音楽的であり、何が創造的かという定義は常に時代と共に変化してきたことが想像できます。

一方で、ポピュラー音楽はクラシック音楽ほど過去の作品をリサイクルしていく文化は根付いていないかもしれません。

過去の作品は演奏されないという数百年続いた音楽業界の常識、慣習を塗り替えたきっかけは19世紀の作曲家フェリックス・メンデルスゾーンです。

彼がその時代に合わせて編曲し、再演したJ.S.Bachのマタイ受難曲は現代に至るバッハという作曲家の再発見と世界的に広く認知される評価へと繋がりましたが、それ以前のバッハという作曲家は一部の地域でしか評価されない忘れ去られた人物でした。

これ以降クラシック音楽は同時代の存命の作曲家の作品以上に、過去の作品を再演する慣習が一般化し、それは現在も続いています。

しかし、クラシック音楽が過去の音楽を演奏する文化となったのは19世紀ロマン派の時代からであり長い西洋音楽の歴史から見れば決して長い伝統ではありません。

19世紀末、トーマス・エジソンによる録音技術が発明されて以来、音楽が録音され、販売されることで、より多くの人々が作曲家の作品に触れ、享受することが可能になりました。これにより、作曲家の影響力や知名度が世界中に広がりやすくなり、音楽がより多くの人々の生活に根付くことにつながりました。

録音技術は過去の作曲家や演奏家の演奏を記録し保存する手段としても貢献しました。

歴史的な録音は後世の作曲家にとって貴重な資源となり、音楽の伝統や進化を理解する上で重要な役割を果たしています。

21世紀にはインターネットによるストリーミング再生も普及し、演奏家の生演奏に依存しない音楽鑑賞という選択肢が一般化した現在、人々はどのような音楽体験を求めているのでしょうか。

これだけ過去の作品が膨大に存在し、すぐに録音音源を再生することが可能な現在、新しい音楽を作るのはなぜでしょうか。

さらに、AIが人間を凌ぐスピードで完成度が高い作品を生み出しつつある状況下で、音楽家は本当に音楽を作ることを期待されているのでしょうか。

世の中から音楽という文化が無くなることは考えにくいですが、死ぬまでSpotifyやApple Musicを再生し続けても全てを聴ききれないほど音楽作品の録音は膨大にあります。

その時代に、音楽の専門家である音楽家が行うべき活動は何なのでしょうか。

Pre-historic algorithmic composition

コンピューター誕生以前のアルゴリズム作曲

The method of creating notes and musical structures logically and computationally using arithmetic rather

than human thought is called algorithmic composition, and its practice began in the 1950s.

It may seem like the sudden appearance of a new concept that has never existed in the history of music, but

an algorithm is a constraint, and in the world of music, it is a concept similar to the style that is

brought about by prohibitions.

Music theory, the study of finding and systematically summarizing the rules inherent in existing musical

compositions, has been the result of various academic studies for centuries of humanity.

On the other

hand,

composers are conscious of creating authorship and style through the rules and restrictions they plan to

impose on their own compositions.

For example, part-writing in counterpoint and harmony also has a great many restrictions, and it is possible

to compose music that fulfills one particular period style just by adhering to its rules, but there are

still too many random elements that may result in tasteless, textbook music unless more restrictions are set

by the composer.

If the composer adheres to most of the prohibitive rules with reference to traditional theory, and then

imposes certain additional detailed restrictions, the work will take on the distinctive style of the

composer's individual style.

On the other hand, it is also creative to design and produce music with sound composition rules that are

completely different from traditional theory.

When taking this approach, it is inevitable to consider the fundamental question of what music is, as one

unfamiliar piece of music after another is created.

John Cage is a prime example of a composer who conceived of the generation of music from rules unknown in

the history of music.

Even though composers are not conscious of the term algorithm, there is a history of using, inventing, and

transforming it over the centuries to create works as a concept of style, which has a close meaning.

Next, we will look at specific musical techniques from a time when computers did not exist, keeping in mind

that algorithms approximate style.

人間の思考ではなく算術を用いて計算で論理的に音符や楽曲構造を生み出す手法はアルゴリズム作曲と呼ばれ1950年代からその実践がスタートしています。

音楽の歴史にない新しい概念が突然登場したように思われるかもしれませんが、アルゴリズムは制約のことであり、音楽の世界でいえば禁則がもたらす様式と同じような概念になります。

既存の楽曲に内在する規則を見つけ出し、体系的にまとめる研究である音楽理論はさまざまな学術研究の成果を何百年にもわたって人類に残し続けています。一方、作曲家は自作に対して計画して与える規則や制限を通じて、作家性や様式を作り出すことに対して意識的な面があります。

例えば対位法や和声法における声部書法も非常に多くの制限があり、その規則を守るだけでも一つの特定の時代様式を満たした音楽を作曲することが可能になりますが、それだけではまだランダムな要素が多すぎて、もっと多くの制約を作曲家が設定しなければ教科書通りの無味無臭な音楽になってしまうかもしれません。

伝統的な理論を参考に禁則を大部分守りつつ、更に一定の細かい制限を作曲家が与えた場合、その作品は作曲家個人の特徴的な様式を帯びたものになっていきます。一方で、伝統的な理論とは完全に異なる音の構成規則をデザインし、音楽を生み出すこともまた創造的です。こういったアプローチを取る場合、次々と聴き慣れない音楽が生まれるため、音楽とは何かという根源的なことを考えることは避けられません。

このような音楽史では未知の規則から音楽の生成を構想した作曲家の代表例はジョン・ケージです。

アルゴリズムという言葉を作曲家は意識せずとも、近しい意味の様式という概念として何世紀にもわたって利用し、発明し、変形させながら作品を生み出してきた歴史があります。

次に、アルゴリズムが様式に近似するという点を意識しながらコンピューターが存在しなかった時代の音楽の具体的技法を見ていきます。

Ancient Greece

古代ギリシア

The mechanism of generatively creating music can be traced back in time as far as ancient Greece to systems

such as the Aeolian harp, which used the force of wind to vibrate the strings.

The sense of scale in which the musical structure is created using only the forces of nature, avoiding

artificial calculations, is similar to that of contemporary art.

Ancient music was an important discipline along with arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy,

Not a few theories, such as musical scales and intervals, have been handed down from the ancient Greeks and

remain in use today.

生成的に音楽を生み出す仕組みは、古くは古代ギリシアで風の力を利用して複数の弦を振動させるエオリアンハープのようなシステムまで時代を遡ることが可能です。

人為的な計算を避けた自然の力のみを利用し音楽の構造を生み出すスケール感は現代アートにも通じるものがあります。

古代の音楽は算術、幾何、天文学と並ぶ重要な学問であり、

音階や音程など現代にも残る理論で古代ギリシアから受け継がれているものも少なからずあります。

Generate music from poems

詩から音楽を生成

The various achievements of Guido d'Arezzo (992 - 1050), an important Italian medieval music theorist, have

left their imprint far into the present day.

The solmization, which represents the height of a note in Do Re Mi, which is taken for granted not only by

musicians but also by many people around the world, was invented by him and takes its name from the initial

letters (Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La) of the punctuation in the lyrics of the chant "Ut queant laxis".

Ut was changed by musicologist Giovanni Battista Doni in the 17th century to Do, meaning Dominus and also

the first letter of his name, to facilitate pronunciation.

The arithmetical composition process presented by Guido in his eleventh-century treatise Micrologus involves

the transformation of a Latin text into a melody under certain rules.

This is a rule-based composition technique in which the composer is not free to create music, but rather the

music is automatically determined depending on the text and lyrics, and is like data mapping in media art,

and is now considered one of the oldest algorithmic composition techniques.

イタリアの中世の重要な音楽理論家Guido d’Arezzo(グイードダレッツォ 992年 –

1050年)の様々な功績は現代にもその爪痕を大きく残しています。

音楽家に限らず世界各地で多くの人が当たり前に使っている音の高さをドレミで表すソルミゼーションは彼が考案したもので、

聖歌「Ut queant laxis」歌詞の区切れ目の頭文字(Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La)から名前が取られています。

なおUtは17世紀に音楽学者Giovanni Battista

Doniによって発音を容易にするためにDominusを意味し、彼の名前の頭文字でもあるDoに変更されて現在に至っています。

グイードが11世紀のMicrologusという論文で提示した算術的な作曲プロセスはラテン語のテキストを一定の規則の元に、旋律に変換するというものです。

これは作曲家が自由に音楽を作るのではなく、あくまでもテキスト、歌詞に依存して音楽が自動的に決定するルールベースの作曲技法でありメディアアートのデータマッピングのようでもあり、現在では最も古いアルゴリズミックコンポジションの一つと考えられる手法です。

isorhythm

イソリズム

Invented by 14th century composer Philippe de Vitry, isorhythm later reached its peak with Guillaume de

Machaut.

This is a compositional technique that combines a set of pitches called colore and a set of rhythmic

patterns called talea to produce complex hochetus and other pieces.

It is a kind of repetition technique,

but since the number of notes in the talea differs from the number of notes in the corolla, it avoids simple

repetition of patterns that could be made close together.

Compositions at that time were required to quote Gregorian chant as Cantus Firmus. While using this sequence

of notes as a corollary, a new rhythmic pattern was produced as a talea, and the two were combined to create

a melody.

The minimalist approach has attracted attention from minimalist composers, and even in the 20th century,

composers such as Reich, Pärt, Messiaen, and Cage have applied isorhythms to their works.

14世紀の作曲家Philippe de Vitry(フィリップドヴィトリ)によって発明されたイソリズムは、後にGuillaume de Machaut(ギョームドマショー)によって頂点を極めます。

これはコロルというピッチの集合とタレアというリズムパターンの集合を組み合せ、複雑なホケトゥスなどを生み出す作曲法です。一種の反復の技法ですが、タレアに含まれる音の数とコロルに含まれる音の数が異なるため、近くできるようなパターンの単純反復を避けることができます。

当時の作曲は定旋律としてグレゴリオ聖歌を引用することが求められていました。この音列をコロルとして使いつつ、タレアとして新たなリズムパターンを製作し、両者を組み合わせてメロディーを作っている状態です。

最小限の要素から最大限の展開を行う特性からもミニマリズムの作曲家から注目され、

20世紀でもライヒ、ペルト、メシアン、ケージのような作曲家がイソリズムを応用した作品を作曲しています。

Canon

カノン

The Renaissance canon is a technique in which the singer begins to sing the theme of a fixed melody at

different times, and the theory is that the harmony is determined by the timing at which the singer

begins.

The algorithm is what controls the timing. Unlike fugues, which are relatively free, canons require strict

imitation of the melody based on a set of rules.

ルネサンス期のカノンとは定旋律の主題を異なるタイミングで歌い始める技法であり、どのタイミングから始めるかでハーモニーまで決定される理論です。

そのタイミングをつかさどるものこそがアルゴリズムといえるでしょう。時には主題のリズムや音程の拡大や縮小も行われますが、カノンは比較的自由なフーガと違い一定のルールに基づいた旋律の厳格な模倣を必要とします。

Musikalisches Würfelspiel

モーツァルトのダイスゲーム

Mozart, the master of classical music, was another composer who composed music using automatic generative

processes.

This was a bit of a fad at the time, as several composers, not just Mozart, were

experimenting

with this kind of thing.

The algorithm inherent in Musikalisches Wurfelspiel is to number the myriad of several bars of fragmented

music and randomly select the order of each fragment using dice.

古典派の巨匠モーツァルトもまた、自動的な生成過程を用いて音楽を作曲した作曲家の一人です。最もこの時代はこういった試みはモーツァルトのみならず何人かの作曲家が取り組んでおりちょっとした流行でもあったようです。

Musikalisches

Wurfelspiel

に内在しているアルゴリズムは断片化された無数の数小節の音楽に番号を振り、それぞれの断片の並び順をダイスを用いてランダムに選び出すというものです。

Twelve Tone Technique

12音技法

Perhaps no compositional technique is more infamous in music history than the twelve-tone technique.

Atonal music, as represented by Arnold Schoenberg and his students Anton Webern and Alban Berg of the Second

Viennese School, eliminated all of the gravity and centrality of sound that was typical of it in order to

explore the next era of tonal music.

In order to make the value of all 12 semitones equal, they revived the concept of note rows and canons that

had existed since the Middle Ages, and succeeded in creating music that kept the probability of occurrence

of all notes equal by performing mathematical operations such as antigravity, retrograde, and inverse

retrograde on the sequence of notes determined by the composer in the matrix.

However, the dissonant music produced by this overly systematic compositional technique continues to be one

of the most controversial sounds in history, often isolated from understanding even by performers who are

supposed to be musicians like the composer.

Webern studied musicology under Guido Adler, and received a degree in musicology from the University of

California, Berkeley, with a thesis on Heinrich Isaak, His interest in the compositional techniques of

polyphony during the Renaissance influenced his structuring of atonal music.

12音技法ほど音楽史上悪名高い作曲技法は無いかもしれません。

アルノルト・シェーンベルクとその弟子のアントン・ウェーベルン、アルバン・ベルクらの新ウィーン楽派に代表される無調音楽は、調性音楽の次の時代を模索するために、その典型である音の重心や中心性を一切排除しました。

彼らは12半音全ての価値を等価にするために、中世以来の音列やカノンの概念を復活させ、マトリクス上で作曲者が決定した音列に対して反行、逆行、逆反行などの数学的なオペレーションを行うことにより全ての音の出現確率を同等に保つ音楽を生み出すことに成功しました。

しかし、この過度にシステマティックな作曲技法が生み出す不協和な楽曲は、史上最も物議を醸し続けている響きであり、しばしば作曲家と同じく音楽家であるはずの演奏家からも理解が得られず孤立することもあります。

なお、op.27変奏曲にて、調性が決定される最小限の要素、トライトーン+1音という条件を満たし次第転調し続けて、無調音楽どころか極度にミニマルな調性音楽とも見ることが可能な究極の音楽を生み出したともいえるウェーベルンはグイード・アドラーに音楽学を師事し、ハインリヒ・イザークに関する論文で学位をえており、ルネサンス期へのポリフォニーの作曲技法への関心が無調音楽の構造化に影響しています。

John Cage's Gamut

ジョン・ケージのギャマット

Continuing to confront the question of what composition is, John Cage used entirely new compositional

techniques based on various concepts, such as chance music and indeterminate music, to escape the old

stereotypes. One of the earliest examples of this is the 20th century application of a concept called gamut,

which has been around since the time of d'Arezzo.

The music was created by sensuously picking up fragments of diverse sound materials, including dozens of

arbitrarily prepared single notes, heavy notes, and chords, and piecing them together in a patchwork-like

fashion.

There are no conventional classical musical conventions.

The next step was to prescribe a strict arrangement for the gamut, using chance operations to move up, down,

left, and right, and finally to choose at random.

Cage's goal was to create a world where music is automatically generated according to rules that do not

easily reflect the author's intentions.

Although Cage initially interacted with and influenced Boulez, who led the European avant-garde movement, he

gradually became more and more devoted to Eastern philosophy and expanded his activities into a far wider

range of fields, including contemporary art, and his unique view of music parted company with the

avant-garde.

作曲とは何かという問いに向かい続けたジョン・ケージは偶然性の音楽や不確定性の音楽など、様々なコンセプトに基づく全く新しい作曲技法を旧来の固定観念から逃れるために使用しました。その初期の例の一つがd’Arezzoの時代以来のギャマットと呼ばれる概念を20世紀的に応用した例です。

あらかじめ恣意的に用意した数十個の単音、重音、和音が混ざった多様な音素材の断片を感覚的にピックアップしパッチワークのようにつなぎ合わせて音楽を生成

しました。

そこに従来のクラシック音楽的な慣習はありません。

次第にギャマットに厳格な配列を規定して上下左右の移動をチャンスオペレーションを使って行うようになり、最終的にはランダムに選ぶようになりました。

ケージが目指したものは、作者の意図が反映されにくくルールに従って自動的に音楽が生成される世界です。

当初はヨーロッパの前衛を牽引したブーレーズとも交流があり影響しあっていましたが、次第にケージは東洋哲学に傾倒したり、現代美術など遥かに広い領域で活動を広げることになり、その独自の音楽観は前衛音楽とも袂を分つことになりました。

Arvo Pärt's Compositional Techniques

アルヴォ・ペルトの作曲技法

The works of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt are also very often systematically generated in an arithmetic

manner.

His works in the tintinnabuli style, such as Für Alina and Berliner Messe, which are based on

two-voice counterpoint consisting of M-Voice, the sequential progression of diatonic scales, and T-Voice,

the main triadic arpeggiation, in order to redefine tonal music, are like Renaissance music, and the 12 The

systematic technique after the 12-tone technique further pushed minimalism in some aspects.

One of his masterpieces, Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten, is a very experimental approach in which the

first violin melody begins with a single note, then expands to two notes, then three, and finally a complete

melody appears.

Again, medieval isorhythms are applied here, and for the fixed two-note tarea rhythmic pattern of one

half-note and one quarter-note in less than one measure, the colore continues to extend to the end.

In

this

way, the repetitions and variations are completely different from the music that loops bar by bar.

Talea

is

expanded to double, quadruple, etc. its size in the voices of the 2nd violin, viola, and cello, which is

also an application of the medieval canon technique.

エストニアの作曲家、アルヴォ・ペルトの作品も算術的にシステマティックに生成されているケースが非常に多いです。調性音楽を再定義すべく、ダイアトニックスケールの順次進行のM-Voiceと主三和音のアルペジエーションのT-Voiceから成る2声対位法をベースにしたFür

AlinaやBerliner Messeなどのティンティナブリ様式の作品はルネサンス音楽のようであり、12音技法以降のシステマティックな技法により、さらにミニマリズムを押し進めた側面があります。

代表作の一つ、Cantus in memoriam Benjamin

Brittenは1stヴァイオリンのメロディーが1音から始まり、2音、3音と一つづつ音列の数が拡張していき、最後に完成系の旋律が姿を現す非常に実験的なアプローチではありますが、そこから生み出される音楽は決して無機質で数学的な匂いがする無調音楽とは異なる美しさや静寂を伴う響きではないでしょうか。

ここでも中世のイソリズムが応用されており、1小節未満の二分音符一つと四分音符一つの2音の固定的なタレアのリズムパターンに対して、コロルは最後まで拡張を続けます。こうすることで小節単位でループしている音楽とは全く異なる反復、変奏が行われていることになります。タレアは2ndヴァイオリン、ヴィオラ、チェロの声部ではサイズが2倍、4倍などに拡大されていて、これも中世のカノンの技法が応用されています。

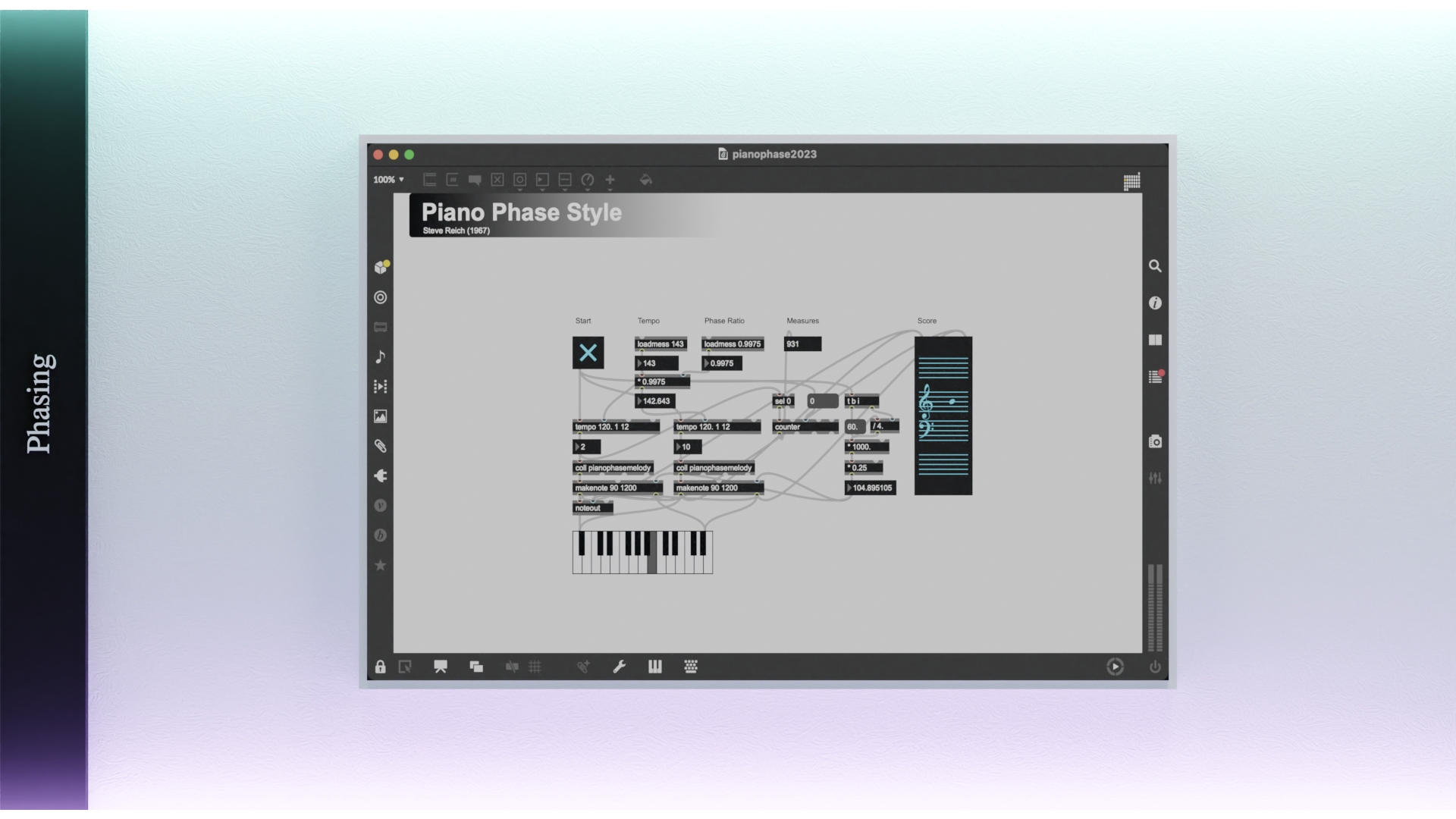

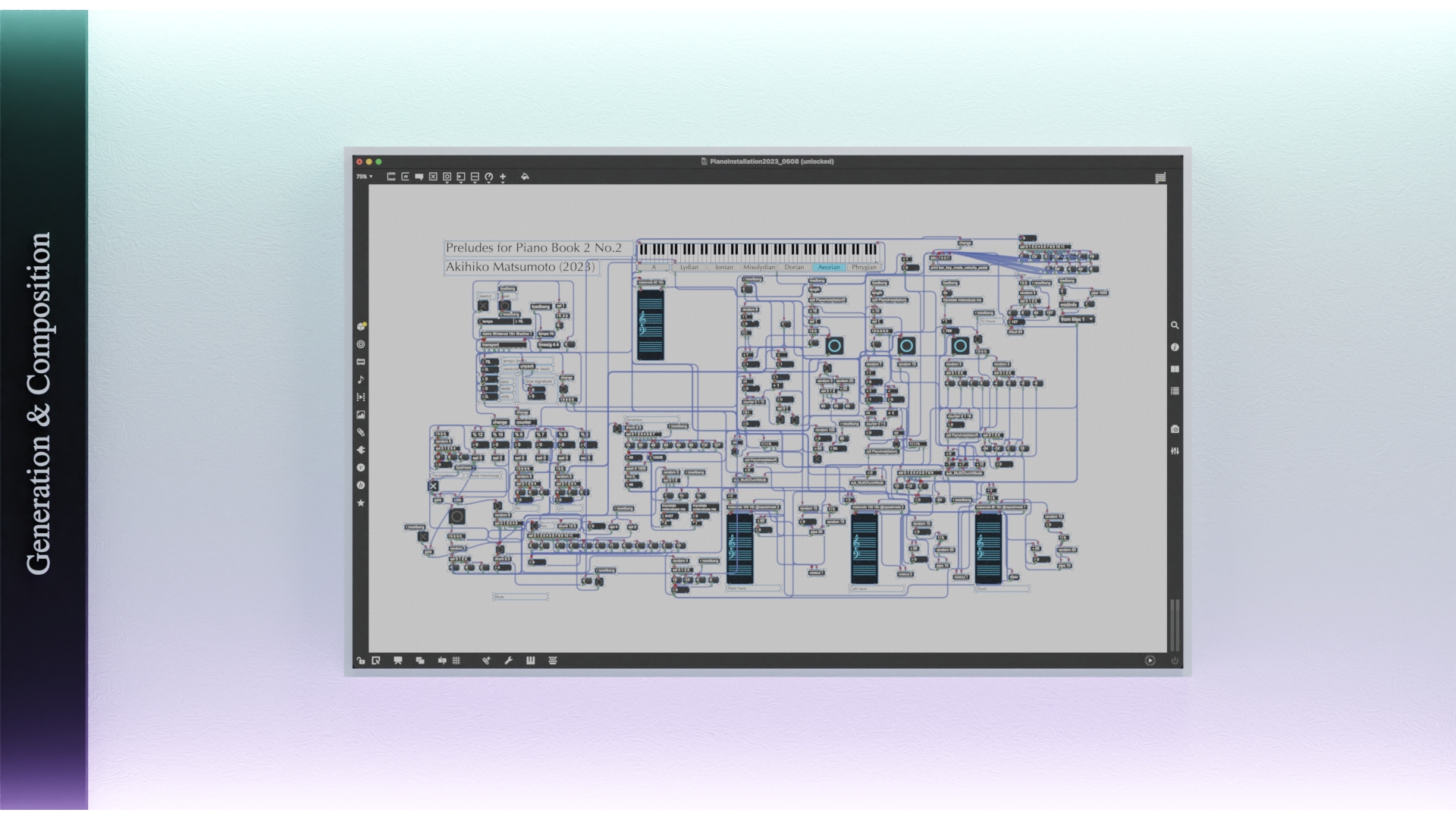

After Computer

コンピューター以降

Through programmatic and automatic composition and generation of compositional algorithms, it is easier to

evaluate the musical style itself that the algorithm encompasses.

Normally, a style cannot be seen unless a number of musical works are created through the act of

composition, but with algorithmic composition, an infinite number of pieces within the same style can be

generated instantly, making it easy to identify the characteristics of a style (algorithm).

Next, we will look at examples of music composed by computer arithmetic since the invention of the computer.

作曲アルゴリズムはプログラムによる自動作曲、自動生成を通じて、そのアルゴリズムが内包する音楽様式そのものを評価することが容易になります。

通常、作曲行為を通じて何作品も音楽作品を作らなければ見えてこない様式も、アルゴリズム作曲を用いれば瞬時に同じ様式の範囲内の楽曲を無限に生成できるため、様式(アルゴリズム)の特性を見抜くことが簡単になります。

次にコンピューターが発明されて以降コンピューターの演算で音楽を作曲した例を見ていきます。

"Illiac Suite" …Lejaren Hiller (1956)

イリアック組曲

The first example of the use of computer algorithms in composition is Hiller's String Quartet, published in

1956 by Lejaren Hiller and Leonard Issacson of the University of Illinois.

In this piece, the Iliac

computer

at the University of Illinois generates pitch, rhythm, and other musical symbols and outputs them as

alphabetical and numeric combinations. This is then translated by human hands to complete the score for a

traditional string quartet. The music for this piece is constructed based on the Markov chain algorithm.

作曲にコンピュータのアルゴリズムを用いた最初の例はイリノイ大学のLejaren HillerとLeonard Issacsonが1956年に発表したヒラーの弦楽四重奏曲です。

この作品ではイリノイ大学にあるイリアックコンピュータがピッチ、リズム、その他の音楽的な記号を生成し、アルファベットと数字の組み合わせとして出力します。これを人間の手によって翻訳し、伝統的な弦楽四重奏の楽譜が完成しました。この作品はマルコフ連鎖のアルゴリズムを元に音楽が組み立てられています。

Iannis Xenakis

イアニス・クセナキス

Xenakis is famous as a composer who used various mathematical logics and probabilistic methods of composing

with computers.

The rest of the piece was composed by algorithmic composition using IBM's 7090 computer.

Other instrumental pieces ST/10, 080262, ST/48-1, 240162, Atrees, and Morsima-Amorsima were written using

probabilistic methods.

クセナキスは様々な数学の論理を用い、コンピュータを使った確率論的手法で作曲を行った作曲家として有名です。

Eontaは強烈なリズム、複雑な和音構造、そして驚異的な音響効果で知られている管弦楽曲ですが、冒頭部分を除いてはIBMの7090コンピュータを用いてアルゴリズム作曲によって作られています。

その他ST/10、080262、ST/48-1、240162、Atrees、Morsima-Amorsimaは確率論的手法を使って書かれた器楽曲です。

David Cope

デヴィッドコープ

David Cope is an American musicologist/composer and the developer of Experiments in Musical Intelligence

(EMI).

EMI

searches its internal database for appropriate melodic fragments, and then connects them according to a

certain musical grammar to generate music.

Furthermore, he has succeeded in analyzing his own past works and automatically generating music in his own

style.

This has given rise to the value that a composer is no longer engaged in a creative act if he does

not create a new style himself.

David Copeはアメリカの音楽学者/作曲家で Experiments in Musical Intelligence (EMI) EMIの開発者です。

EMI

は内部のデータベースから適切なメロディ断片を検索し、ある音楽文法に従って接続し音楽を生成していきます。

更に彼は自身の過去の作品を分析し、自分の様式での音楽を自動生成することにも成功しています。

このことは作曲家はもはや新しい様式自体を作らなければ創造的行為を行っていることにはならないという価値観を生み出しました。

Practice

実践

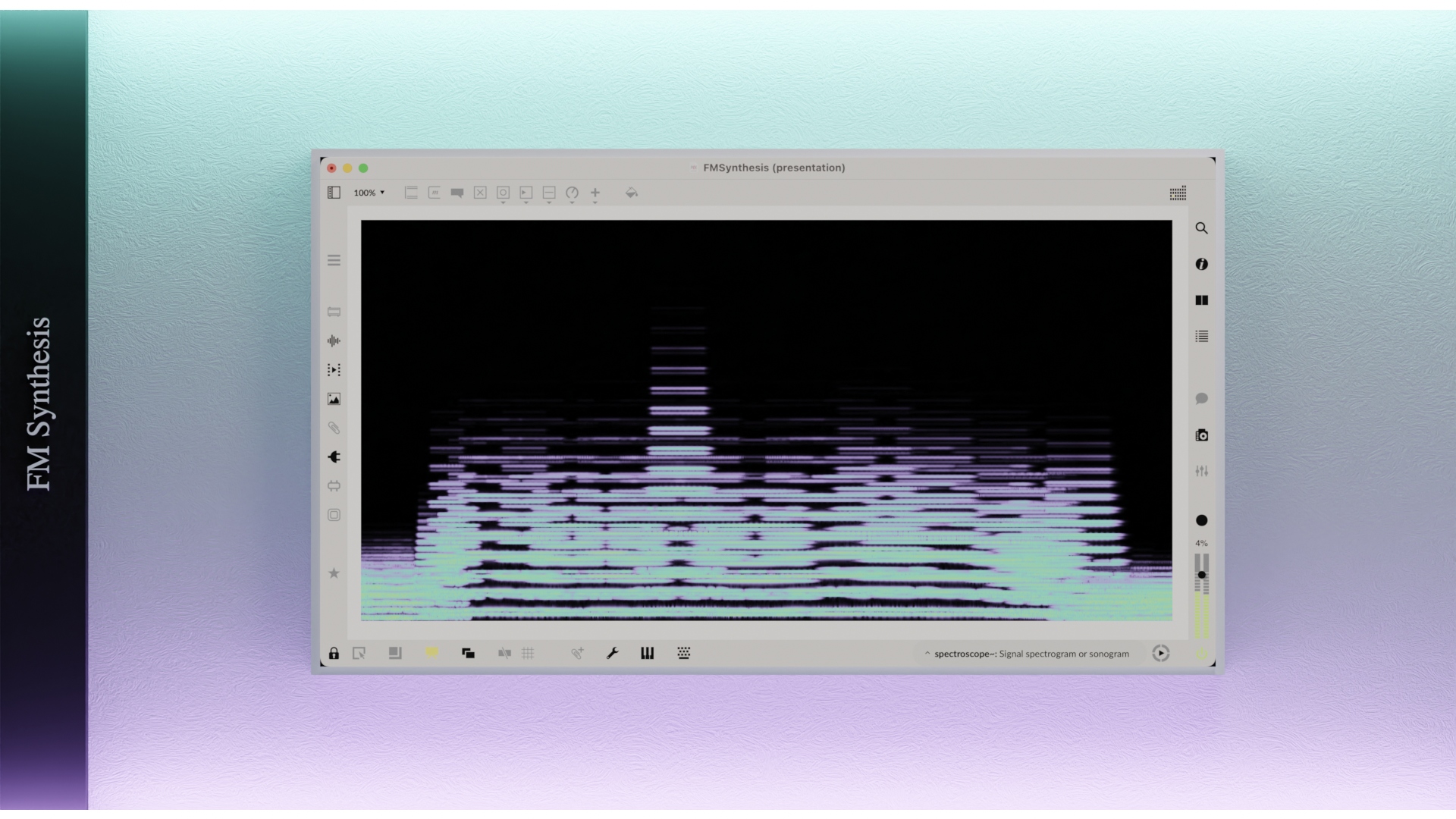

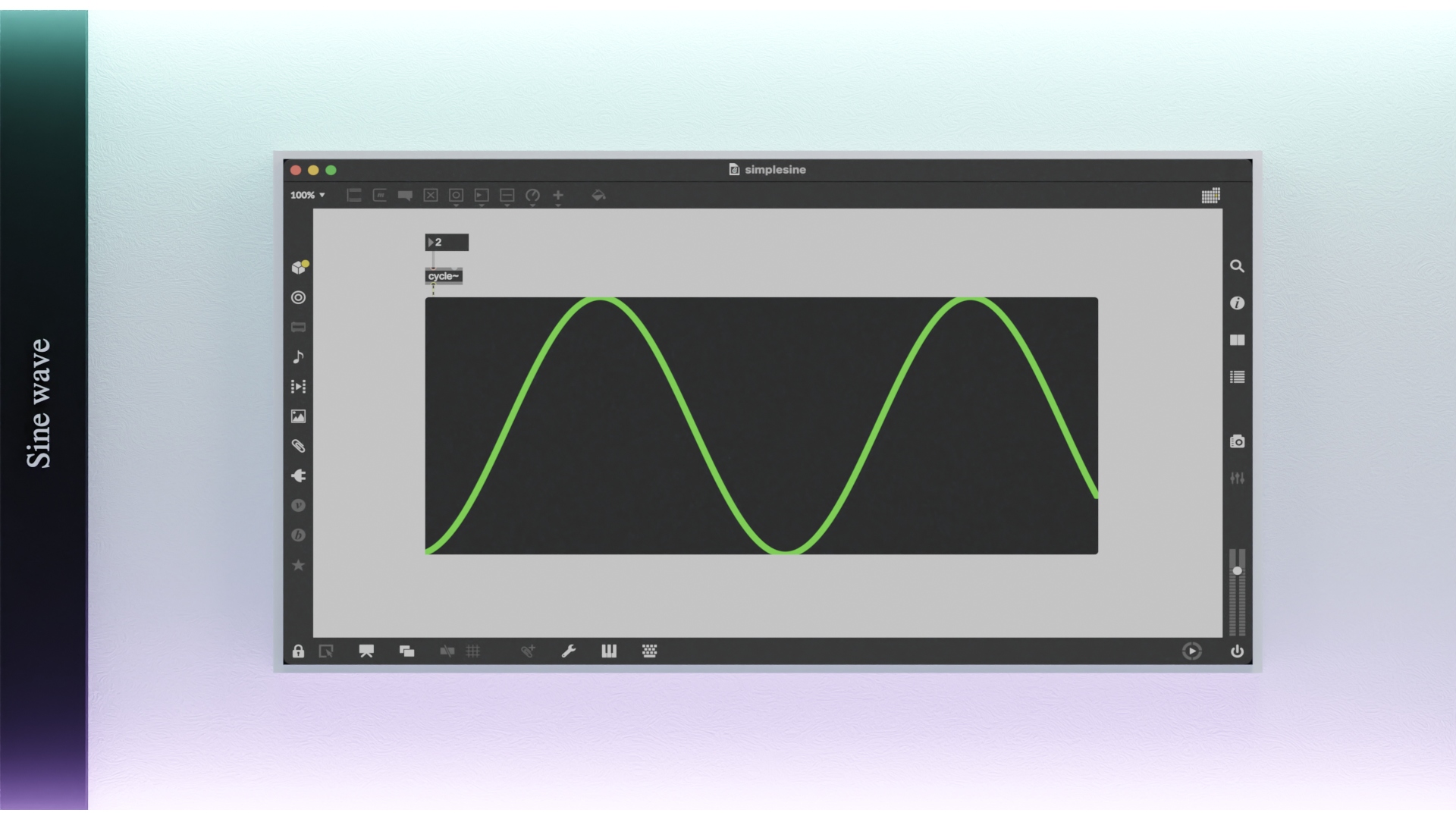

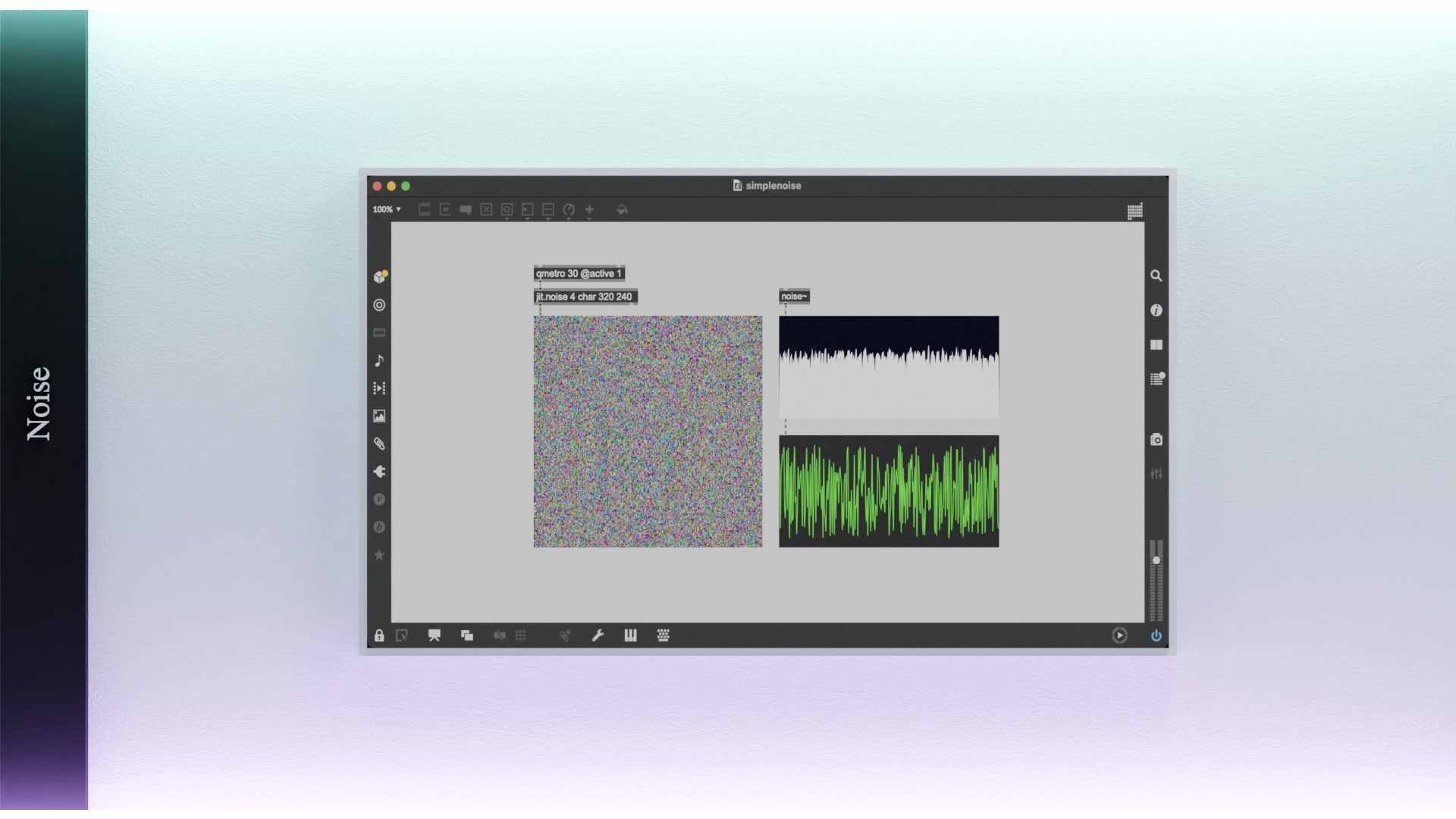

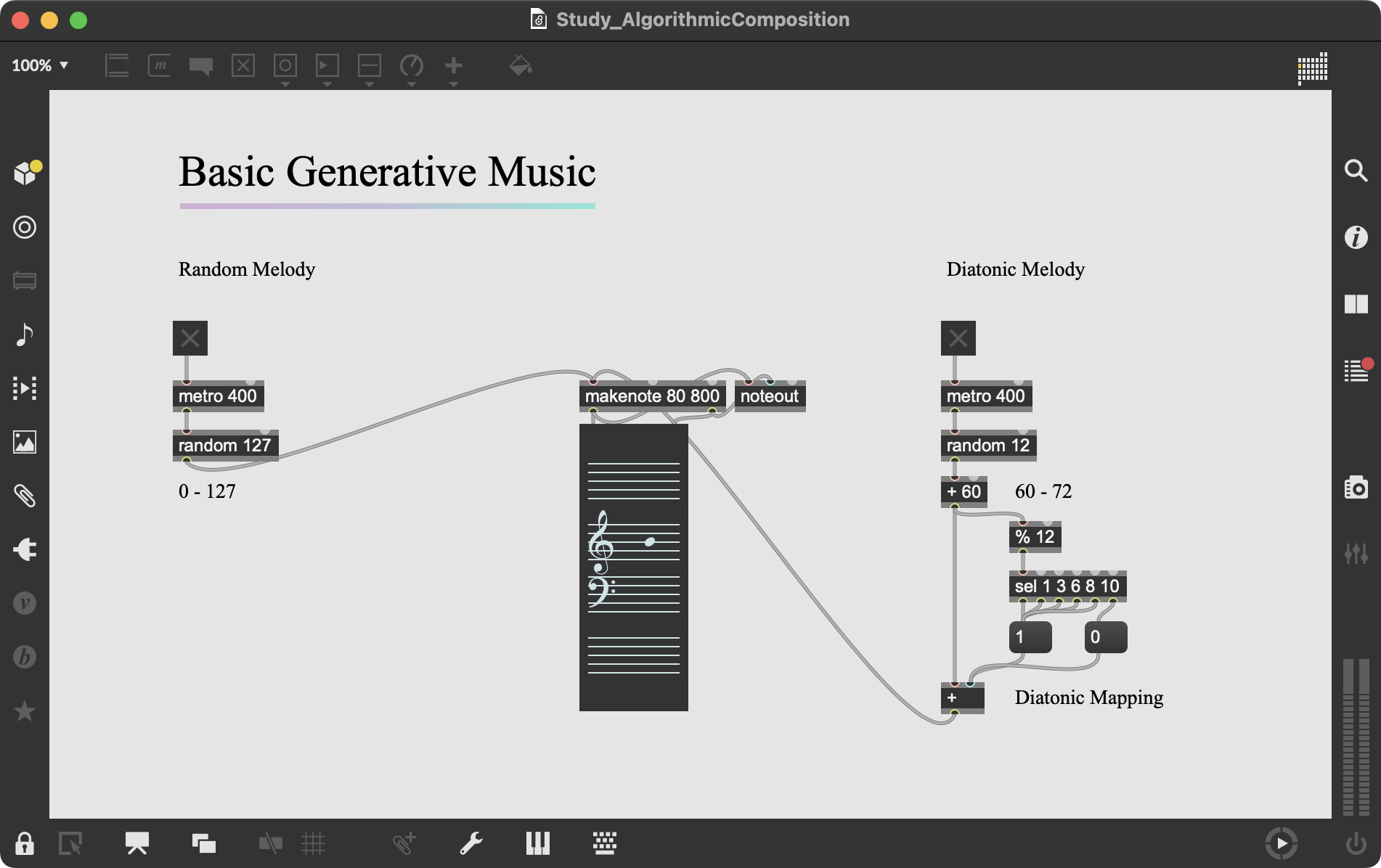

I have prepared a simple melody generation program to let you experience that the algorithm is a style, and

that the constraints shape the style.

While the left side of the program is just a random selection of note heights without any order, the right

side first restricts the range to one octave and then restricts the pitch to the diatonic scale.

This may

not

yet be enough to call it music, but you can experience how placing restrictions on mere noise is approaching

music.

アルゴリズムがすなわち様式であり、制約が様式を形作るということを体感してもらうための簡単なメロディー生成のプログラムを用意しました。

左側は何の秩序もなくただランダムに音の高さが選ばれるのに対して、右側はまず音域を1オクターブに制限し、次にピッチをダイアトニック音階に制限しました。まだこれだけで音楽とは言えないかもしれませんが、ただのノイズに制約を与えることが音楽に近づいていくことであることを体感できるのではないでしょうか。

Conclusion

まとめ

What is music and what is creative? The fact that we are living in an era of drastic changes in values may

not actually be a special era, given the several hundred years of Western music history.

The human ear can no longer distinguish between music generated by computers with the latest technology and

music composed by trained musicians on the basis of the piece alone.

As long as composers stay in the same style and compose music, they may be spending a great deal of time

composing works that are far more error-prone and less accurate than music generated by machine learning and

style-mimicking algorithms.

Can we really call this an artistic, creative, and worthwhile act?

And if a non-human composer presents a new style, will there be listeners who will persevere with unfamiliar

and strange sounds?

It is becoming increasingly important for composers to consider what creativity, rights, and originality

are.

何が音楽か、何が創造的か。価値観が大きく変わる時代に我々は生きているという事実は、実は数百年の西洋音楽の歴史を考えると特別な時代とは言えないかもしれません。

人間の耳には最新の技術でコンピュータが生成した音楽と、訓練されている音楽家が作曲した音楽とを比較した場合、楽曲だけではもはや区別ができません。

作曲家は同じ様式にとどまって音楽を作曲する限り、機械学習や様式模倣のアルゴリズムに生成させた音楽よりもはるかにミスが多く精度が低い作品を作曲することに多大な時間を費やしているのかもしれません。

これを芸術的、創造的で価値がある行為とはたして呼べるでしょうか。

また、人間である作曲家以外が新しい様式を提示したとして、聴き慣れない奇妙な音に根気強く付き合ってくれるリスナーはいるでしょうか。

創造性とは何か、権利とは何か、オリジナリティとは何かを考えることがますます作曲家にとって重要なものとなってきているのではないでしょうか。

Reference

Curtis Roads. The Computer Music Tutorial. MIT Press https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262680820/the-computer-music-tutorial/

Charles Dodge. Computer Music: Synthesis, Composition, and Performance. Schirmer Books https://amzn.to/463ehCu

Joseph N Straus. Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory. Pearson https://www.pearson.com/en-gb/subject-catalog/p/introduction-to-post-tonal-theory-pearson-new-international-edition/P200000008899/9781292055565

Peter Burkholder, Donald Jay Grout, Claude V Palisca. A History of Western Music. W W Norton & Co Inc https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393668179

David Cope. Computer Models of Musical Creativity. MIT Press https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262534109/computer-models-of-musical-creativity/

Richard L. Crocker. A History of Musical Style. Doverhttps://store.doverpublications.com/0486250296.html